CCP. Chinese Communist Party. It’s a rather frank name, leaving little to the imagination. Since 1949, China has been a communist state, born out of the socialist revolution. Yet surprisingly, many would argue that today, China’s economy is an exemplification of capitalism and ironically demonstrative of a successful capitalist state. This article aims to break down the history of China’s economic growth in a simplistic manner to economics newcomers, and then discuss this growth model’s adherence to communism.

A Note on Growth Models

Every country has a growth model. It is this mechanism which explains how exactly a nation’s economy grows (typically measured by changes in its Gross Domestic Product). Previously, wage-led growth models held prevalence as increasing wages enabled higher spending and consumption, which stimulated economic growth. However, wage-led growth presents an uncomfortable amount of risk, as wages can stagnate as a side effect of the cyclicality that comes with our economic system (the trade cycle), and economies reliant on wage growth are susceptible to violent inflation. Clearly, wage-led growth is risky, and economies are better led on certainty than risk. The answer to this problem is multifaceted, and different contexts give differing answers. In much of the West, the answer came in two words – consumption and debt. For others, the answer was exports. For China, the answer was: “Why settle for one?”

A Brief History of China’s Export Industry

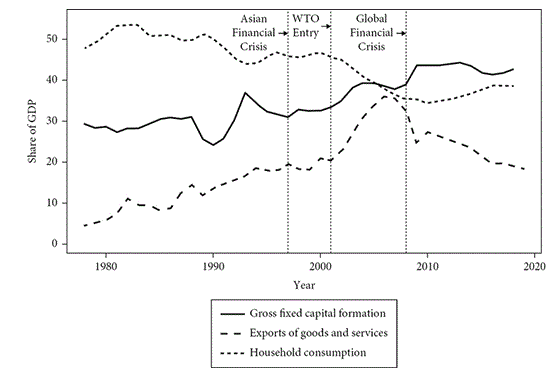

For a nation like China, which saw a wave of Western manufacturing offshored into its borders, in conjunction with a large labour force and cheap capital, exports were an attractive and natural solution in the aftermath of the destructive Mao era. Throughout the 1990s, China shifted its economic zones away from the countryside and towards urban coastal areas. Through this process, they drove down protectionism in the form of loosening tariffs and other regulations, opening the nation to foreign enterprises. These coastal zones became powerhouses of low-cost production, attractive by virtue of their cheap capital, labour, and land. This was the making of the conditions we know today, whereby foreign firms export their manufacturing processes to the Chinese coast, attracted by the lucrative cost-saving China offers. Thus, the 1990s represented a shift towards an export-oriented growth model. Figure 1 below demonstrates the sharp increase in the export share of China’s GDP, almost doubling across the decade. Simultaneously, household consumption experienced a steady decline, falling from above 45% to below 40% of the GDP, reflecting a reduced reliance on domestic consumption. These trends demonstrate the growing importance of exports in driving China’s economic expansion during this period.

However, the conditions necessary for China to be fully exposed to the global economy had not yet been achieved. While the coastal areas of China underwent integration and globalisation as foreign capital poured in, the interior regions of China remained sharply insulated from the world. Although the coastal special economic zones had their protectionist policies reduced, the interior remained very much subject to tariffs and red tape. This division allowed foreign firms to dominate coastal areas, while state-backed enterprises found success in the interior areas. The binary, however, would not endure as China entered the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001, introducing significant trade liberalisation processes to the country.

China’s integration into the international system played a pivotal role in amplifying its export growth strategy. The WTO’s commitment to trade liberalisation meant that import tariffs fell to below 10% from numbers above 30%, and in the next 6 years, the nation would see exports as a share of its GDP rise by 15%. This ushered in the ascendancy of export-oriented growth with a fall in the reliance on consumption, with it decreasing by 9%, lowering it to 36% as a share of GDP. The entry into the WTO had two major effects – firstly, privately owned enterprises gained a much larger share of exports, where previously they had been sidelined in favour of state enterprises. Secondly, there was an incredible expansion of foreign enterprises, dominating China’s exports. However, two major events, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, would signify that this export-oriented growth model was not synonymous with economic sustainability.

China’s Economic Dynamism

The signs that embarking upon this path of export reliance spelled trouble for the Chinese economy came in the late 1990s. Between 1997 and 1998, a financial crisis shocked East and Southeast Asia, shrivelling FDI flows in China. China suffered, but not severely. The question is, why?

China is a large country. Spanning 9.3 million square kilometres, it is the 4th largest country on Earth by landmass. In conjunction with its colossal landmass, China’s population in the 1990s was (and still is) immense, at over 1.1 billion. Surely then, coastal export strategies were not the sole limitations of government policy. Land, after all, is a form of capital (at least it can be), and given China’s large size and highly ruralised society, this was the next obvious form of growth to turn to. Thus, pivotal to China’s growth in this era was also the commodification of land. Ownership became distinct from use rights, meaning that land could effectively be developed via state investment for means of housing and infrastructure. Urbanisation, too, was a key result of this policy. Such investment creates a macroeconomic feedback loop. With employment skyrocketing in the construction industry, which itself saw soaring demand from the state as they were tasked with infrastructural growth, workers on average had more disposable income to consume, stimulating demand and vitalising the economy in times of external faltering that weakened the nation’s export industry. Better still, whereas such policy often becomes decentralised due to the privatisation of land, this variant practised in China ensured centralised control by Beijing over how much land was commercialised – the private enterprises that controlled this new infrastructure did not own the land; they merely possessed use rights to the land. Regardless, this new policy had interesting implications for the “communism” of the Chinese state.

The financial crisis of 1997 gave a clear warning: China was too dependent on exports for its growth. The government had choices to pursue alternative growth strategies, yet ideological legitimacy hindered the availability of these choices. Low (private) consumption would have to be reversed, meaning additional centrality being placed on the private sector, antagonising foundational communist ideals. Wage-led growth models were out of the question, partially due to the aforementioned reason of ideological incoherence, but also because wages in China were already being repressed. Thus, in this environment, the government turned to public spending and state-led investment as a model of growth to work simultaneously with the coastal export model. The need for economic dynamism was reinforced by the 2008 financial crisis. The crisis devastated business and consumer confidence, plummeting aggregate demand from foreign nations. Consequently, China’s export model suffered. To counter this, Beijing drew on its historical success and injected over $580 billion into the economy, primarily through infrastructure spending. The crises of 1997 and 2008 demonstrated the weaknesses of the growth model singularity, enhancing the state-led investment aspect of the economy and solidifying its place as part of the dualistic growth of China. The evolution of China’s dual growth strategy further blurs the line between economic pragmatism and ideological legitimacy, raising crucial questions about the true nature of China’s political economy.

China’s Political Economy

In late 2023, an article was published in the Financial Times arguing that the paradoxical contradiction of China’s formal communism, which is now working in tandem with virulently successful state capitalism, posed an existential threat to the Chinese state. So, is China a communist state or a capitalist one?

Communism in the economic sense is somewhat rigidly defined. If the state does not control the factors and means of production, then it is not communist. It might be socialist in a sense, but not communist. China’s economy is incomplete without the state – indeed, the state decides on most major business decisions, and many of the nation’s largest corporations are state-owned. To speak of the Chinese economy without state intervention would be to speak of no economy. But this in and of itself is not proof of communism – the state can have a heavy hand and still adhere to capitalism. In contrast to the rigidity of communism, capitalism is far more heterogeneous in its varieties. Capitalism is not monolithic, rather, it is a dynamic system that evolves and adapts to the multitude of cultures and societies that it interacts with. The Chinese economy relies on the market for its growth according to Chinese economist Weijian Shan, and the profit motive is intrinsic to its export-led growth model. Similarly, its state-led investment growth partially hinges on the consumption impetus of the workers who benefit from the multiplier effect of government spending. China receives the largest amount of Foreign Direct Investment in the world, had more billionaires than the U.S. in 2020, and has embraced private enterprise as a mechanism of growth, meaning that the state in fact does not own all the means of production, nor is this production centralised. While it is true that the Chinese government does heavily subsidise private enterprise, granting it a degree of control unfound in most Western economies, indirect influence cannot be equated with asset ownership. China’s unique set of circumstances and growth story have given birth to this hybrid model: a socialist market economy, or a nation run by “state capitalism.” Call it what you will, but whatever it is, it isn’t communism.

As China furthers itself from communism under the directive of the Chinese Communist Party, one must then wonder if indeed China’s government will suffer a loss of legitimacy at some point in the near future. The state has three choices.

Firstly, it may revert to a more centralised and planned economy. It is hard to tell what this would look like, but such reform would probably take the form of immense nationalisation of private enterprises and the lowering of the nation’s reliance on FDI. Such an option is highly unlikely. Contrary to popular opinion, China does seek the maintenance of the status quo; it must, for its entire economy hinges on its ability to utilise multilateral institutions like the WTO to exploit liberal trade practices. A reversion to hardline communism would see a decrease in living standards, the decimation of the middle class and a potential regression to the famines of the 1960s. Such conditions breed an environment prime with revolutionary fervour. Additionally, the growing middle class facilitates the weaponisation of China’s domestic market internationally. The mass consumption of China’s growing middle class relates to the theory of weaponised interdependence where, through other nations’ export reliance on China, it can dictate whether or not its middle class receives access to such exports. Cutting off China’s domestic markets from a nation’s exports would devastate export revenue figures.

Secondly, the state might abandon its communist heritage and formally embrace the hegemony of the market in its economic growth story. This, too, would be unlikely as of now, since the Chinese government’s legitimacy would certainly be called into question. A revolutionary government taking power from the bourgeoisie only to give it back to them would be grounds for one to claim it an illegitimate government. One might then see the answer in political liberalisation and a transition to democracy. This path has the potential to bear more fruit as the state’s legitimacy no longer hinges on ideological adherence. However, while political liberalisation would not work if the state were communist, its effect on a nation with a socialist market economy is yet to be seen. As seen with the USSR, communism often hinges on authoritarian order, and when that falls, the nation falls. Whether or not the same would apply to a socialist market economy where the government’s heavy hand is axiomatic remains to be seen.

Thirdly and perhaps most likely, China will continue to tightrope its way domestically and internationally in a hybrid fashion, a walking paradox of an economy which calls itself one thing yet practises another. This seems plausible as the impetus for formal change is simply not there. After all, China now rivals the United States in its economic capabilities, and despite flaccid attempts by Western powers to impose protectionist measures on Chinese exports, China’s grip on the global economy remains iron tight.

Conclusion

China’s economy doesn’t fit the rigid parameters of Communism. Rather, it is a multifaceted system that integrates notions of centralised state intervention with free market economics to create a dynamic growth model that places its trust in no single economic generator. Effectively utilising its natural resources and geographical endowment, China has taken full advantage of its context to produce an economy that relies on export-led growth in conjunction with state-supported investment, primarily by way of land and infrastructure. The resulting binary that has formed speaks to a departure from the revolutionary throes of communism, and while China’s legitimacy as a state might still abstractly rest on an abstract loyalty to Maoist ideologies, its practical economic action is one that glorifies the free market, weaponising its domestic markets and enticing foreign consumers with tantalisingly low-priced exports. Thus, the burgeoning question of ‘communism’ or ‘capitalism’ has an answer. Economically, the state is characterised by capitalism gripped like a vice by the state, but not so much so as to verge into communism. This socialist market economy is unlikely to change anytime soon as China seeks the maintenance of the status quo: a nominal Communist state which uses capitalist growth to dominate the global economy.

By Aadam Hashmi

Cover Image: Shealah Craighead