A Cure for Cancer: Analogising Israel’s Occupation of Palestine and Investigating Accountability

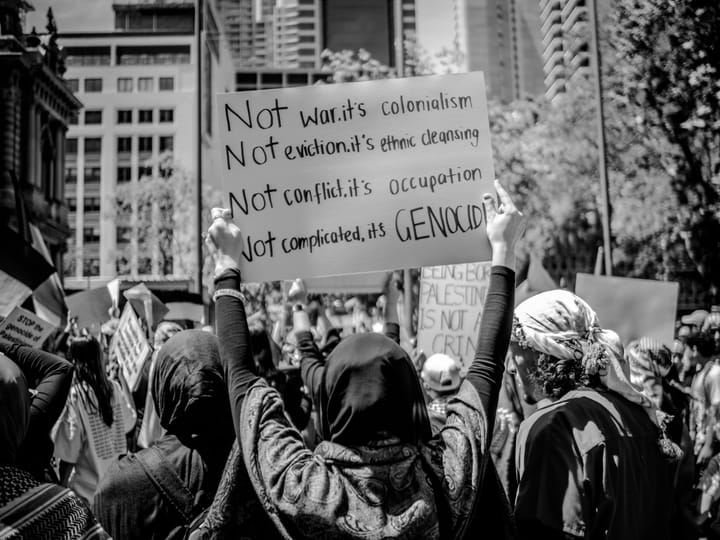

Israeli leaders of the last few decades have been allowed to continue unimpeded in their attempts to abolish Palestine. Is it possible to hold the state accountable?

Israel’s occupation of Palestine does not have many comparisons; the scale and history of it stretch far beyond comprehension. It is often one of the reasons why the situation is described as complex. However, what can be analogised is the character of the occupation.

Throughout the 1990s, in a series of successive wars, Serbia attempted to consolidate its land and power by invading Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo. They were repelled in all these attempts, primarily by the owners of these lands, at great costs. However, it was not the case that Serbia was overwhelmed and pulled out – it was arguably forced to cease and desist due to numerous indictments of their leaders.

The idea that individuals and leaders of movements are held accountable for their actions is not a new one, but a severely underutilised one. Israeli leaders of the last few decades have been allowed to continue unimpeded, and sometimes even supported in their attempts to abolish Palestine. Holding the senior ministers and generals of Israel accountable would set a strong precedent: they cannot hide behind the war machine they run.

The International Court of Justice: Attempts at Accountability

South Africa recently launched a case with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against Israel on the claim of genocide. Sure, in the best-case scenario, the court case would force Israel to comply under investigation and tone down its approach. However, the ICJ does not have a strong track record of effectiveness – in 2003, when Israel began to construct walls within the occupied Palestinian territory, the ICJ merely advised that the intrusion was wrongful, but did not make any statement regarding the occupation, despite the fact that the court supposedly aimed to support the establishment of a Palestinian State.

The ICJ was similarly involved during the Serbian invasions.

Serbia and the ICJ

In the 1990s, Serbia and Montenegro, under the leadership of Slobodan Milošević, attempted to reunify the broken-down Yugoslavia by invading Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo. After the international indictment of Milošević (plus the political instability within Serbia), Serbia had no choice but to withdraw.

Throughout the years after, the ICJ investigated Serbia on behalf of Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. As for Croatia, the ICJ concluded that ‘the existence of an intent to destroy…the national or ethnic group of Croatian Serbs’ could not be established. Serbia could not be charged with genocide or attempted genocide.

The existence of an intent to destroy, in whole or in part, the national or ethnic group of Croatian Serbs had not been established in this case. In particular, although acts constituting the physical element of genocide had been committed, they had not been committed on a scale such that they could only point to the existence of a genocidal intent. The Court found that neither genocide nor other violations of the Convention had been proved. Accordingly, it rejected Serbia’s counter-claim in its entirety.

- Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Croatia v. Serbia)

For Bosnia and Herzegovina, however, the ICJ found compelling evidence that Serbia had committed genocide, or had not taken adequate measures to prevent such genocide from taking place, specifically against Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica.

As for the obligation to punish acts of genocide, the Court found that a declaration in the operative clause that Serbia had violated its obligations under the Convention and that it must transfer individuals accused of genocide to the ICTY and must co-operate fully with the Tribunal would constitute appropriate satisfaction.

- Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro)

The Court found no appropriate way of charging Serbia with genocide, except by enforcing accountability on a few individuals that were deemed responsible for it.

Should We Hold Individuals Accountable?

Milošević was indicted in 1999 towards the end of the Kosovo war, and taken to court in a UN international criminal tribunal. After this point, Milošević’s troops began to reduce their activities and eventually pulled out of Kosovo. Milošević’s charges included failure to prevent genocide, and deportation and displacement of people – actions officially recognised as war crimes, and actions akin to Israel’s treatment of Palestine.

Another instance where a leader was removed, allowing for the possibility of peace, was the indictment of the former general of the Republika Srpska (Serb Republic), Ratko Mladić, who was charged in July 1995. By October, fighting in Bosnia came to a stop, and discussions for a lasting peace were concluded in December of the same year.

As for the war criminal Mladić, he escaped and evaded arrest for over a decade. His capture was one of the pre-conditions for Serbia to be considered for membership in the European Union.

What to do about Israel: Holding Netanyahu Accountable

Last year, Israeli civilians took to the streets protesting and burning flags, objecting to Benjamin Netanyahu's political tactics which disrupted democracy. The riots were triggered when Netanyahu pushed a bill that would “give the government decisive control over the committee which appoints judges”, severely undermining the democratic system, while increasing authoritative power for the PM who, at the time, was also being charged with wide corruption. At the time of writing this, amidst all the chaos and distraction, Netanyahu's bill was denied by the Israeli Supreme Court.

This decision, along with the riots, are an obvious indication that the actions taken by state actors are not representative of the general consensus. Therefore, the individuals responsible for the genocide of Palestinians must be held accountable.

The Many Failures of Israeli Leadership

Lastly, I offer some points and charges [1] [2] [3] which can be directly attributed to Israeli governance, and serve as evidence of Israeli leadership failure:

- Failing to prepare for October 7th

- Responding with disorganised and excessive force, resulting in the deaths and casualties of many Israeli citizens at the hands of the IOF

- Refusing to investigate said incident

- Spreading unverified and false information with the intention of provoking its population instead of alleviating social unrest

- Creating safe zones, and then violating them

- Targeting hospitals and UN facilities

- Failing to make attempts at saving hostages

- Directing attacks to maximise casualties

- Directing attacks to cripple basic necessities

- Failing to reprimand units, soldiers and snipers who cross the line

- Failing to honour ceasefire agreements

As Izetbegović, former president of Bosnia and Herzegovina says in his recount of the Yugoslav war period, “Do not say that everyone is guilty in the same way, because it is a historical lie. A lie does not help. It only enables confusion to grow.” Likewise, we should acknowledge the real perpetrators of terror, and hold them accountable.

Conclusion

Netanyahu and several senior government officials were responsible for forcing a population away from their homes and land into concentration camps. They then explicitly stated that the overcrowded population must be displaced further south – a chargeable crime against humanity.

The apartheid state has been repeatedly allowed to overstep its boundaries, and the directors of its aggressions have been encouraged to pursue their goals without taking ownership of its failures. When Israeli officials are charged for their crimes and begin to feel the weight of their responsibility, only then can Palestinians begin to think about peace and, perhaps, even justice.

By Hamzah Islam

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of The PublicAsian.

Comments ()