A Sad Shot of Truth: How the Murder of Japan’s Longest Serving Prime Minister Unmasked the Unification Church

On July 8th 2022, Tetsuya Yamagami fired a bullet that shook the very foundations of Japanese politics. This article delves into Yamagami’s motives, and explores the Church’s extensive influence over Japanese society and politics, including the deep ties with Shinzo Abe's family.

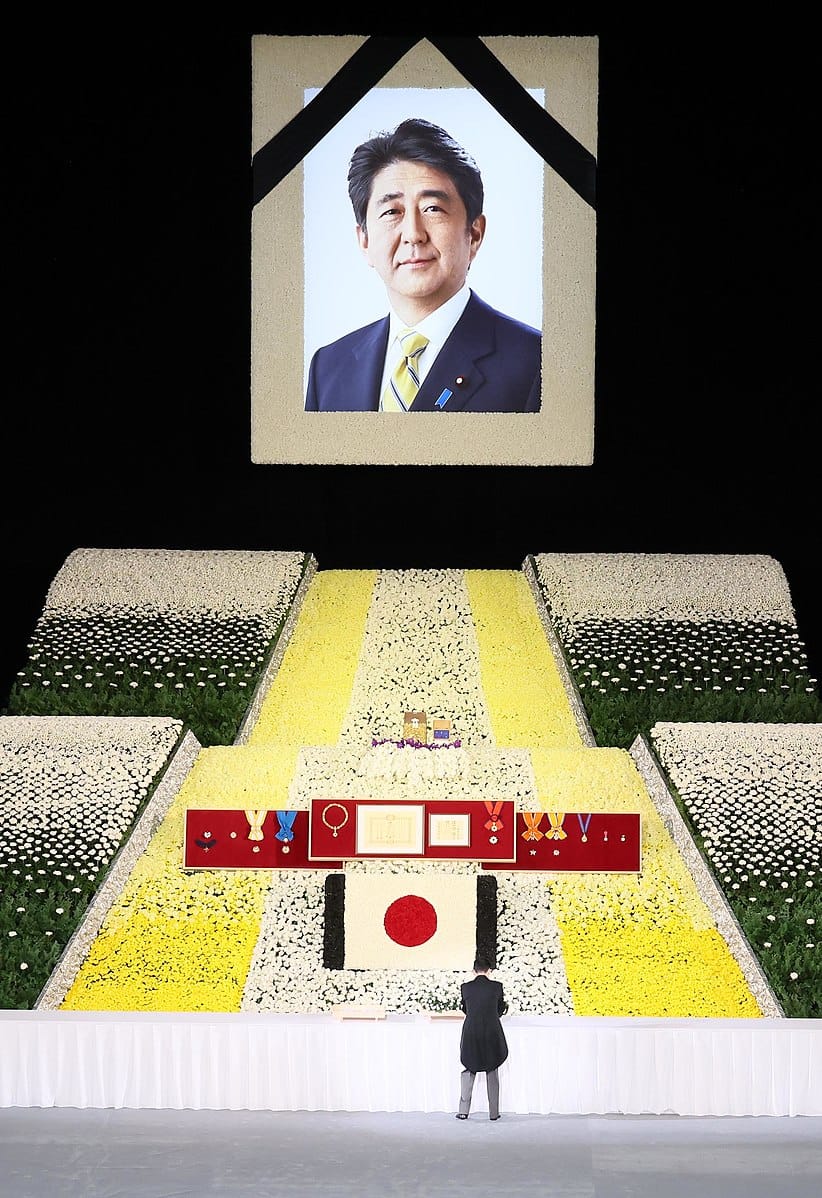

On July 8th 2022, Tetsuya Yamagami fired a bullet that shook the very foundations of Japanese politics. The nation’s longest-serving Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, was dead. This shocking assassination, a rarity in a country that saw just one gun-related death the previous year, was only the first ripple in the Japanese political arena: this single gunshot broadcasted to the world the generational ties Japanese politics had with the controversial Unification Church (UC), officially known as the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification. This article delves into Yamagami’s motives, rooted in personal tragedy and financial ruin, and explores the Church’s extensive influence over Japanese society and politics, including the deep ties with the Abe family. We unravel a narrative that ponders the consequences of the thin lines between religion and politics in modern Japan.

Yamagami's Motives

Image: The Japan Times

Yamagami was born into a well-off Japanese family. His grandfather had founded a company, where his father was a company executive. But tragedy struck when he was only four years old: his father committed suicide, and his mother then joined the UC. She would then go on to donate approximately 100 million yen (around $700,000) to the UC, which had largely come from the life insurance from his father’s death. In 2002, his mother sold company property worth 40 million yen, decisively bankrupting the family. By this point, it was clear that Yamagami’s dreams of going to university had been ‘shattered’. According to Yamagami’s uncle, he stopped giving the family money for necessities such as food and education, as Yamagami’s mother would redirect the money to the Church instead. She allegedly continuously pestered Yamagami’s uncle to donate to the Church as well.

Yamagami’s mother continuously prioritised the UC: despite receiving news that Yamagami had attempted suicide, she chose not to return from her trip to South Korea. According to his uncle, Yamagami’s suicide attempt was motivated by his desire to help his impoverished older brother who had lost sight in one of his eyes due to cancer, thinking that the potential life insurance payout could help him get treatment. Yet, tragically, three years later in 2005, Yamagami’s older brother himself committed suicide. In 2019, Yamagami tweeted that his grandfather blamed his mother for the family’s woes.

“What’s most hopeless is that my grandfather was right. But I wanted to believe my mother.”

Yamagami harboured great resentment towards the UC, but why did he target Shinzo Abe? In the fallout of Abe’s murder, the generational ties between the Church, Abe’s family, and his party were thrust into the public eye.

Church and State, an Unholy Alliance in Postwar Japan

Image: The Asahi Shimbun

In the wake of the Second World War, Japan found itself in the crosshairs of the Cold War. With its new overlord, the US, vehemently against communism, the political elite of Japan adopted a similar stance. In 1968, Sun Myung Moon, who founded the UC in 1954, established the International Federation for Victory over Communism (IFVC) in Seoul and Tokyo. The IFVC would then cooperate with right-wing Japanese politicians, who took advantage of the Church’s manpower for political campaigns. A symbiotic relationship began, where in exchange for this manpower, politicians would defend the Church against criticism.

One of the most proactive of these politicians was Nobusuke Kishi, Abe’s grandfather, and former Prime Minister of Japan. It was reported that when the UC first entered Japan, its headquarters were right next to Kishi’s house in Shibuya, and an FBI report in 1975 also revealed that Kishi was one of the heads of the Japanese branch of the IFVC. Around 20 years after the Church had moved in next door to him, Kishi appealed to US President Ronald Reagan, requesting the release of Moon who was imprisoned for violating US tax laws. Kishi wrote to Reagan, pleading with him to release Moon ‘by all means from his unfair imprisonment as soon as possible’, he went on further describing Moon as ‘a genuine man, staking his life on promoting the ideals of freedom and correcting communism’, and that ‘His existence is, and will be in the future, a rare, precious and indispensable one for the maintenance of freedom and democracy’.

Nobusuke Kishi's letters to President Reagan / Source: Reagan Library

Abe’s father, Shintaro Abe, is also reported to have had ties to the Church. On the 26th of July 2022, Abe’s younger brother (and the defence minister at the time) admitted that he had received aid from the Church in past elections. In terms of Abe himself, in September of 2021, he sent a video message to the UC, praising them for their focus on family values and work on peace in the Korean peninsula. However, Tomihiro Tanaka, the head of the UC branch in Japan, claimed that Abe was not a member nor an advisor, though he did cede that Abe had sent messages to Church-affiliated events, as well as expressing support for the Church’s ‘global peace movement’. Given that Abe’s grandfather, father, and younger brother are all alleged to have had links to the Church, Tanaka may have been downplaying the affiliation between the organisation and Abe himself.

It was not just Abe’s family that fostered connections with the Church, but also a sizeable swath of the Japanese political landscape, including his political party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). According to an internal survey, a staggering 179 out of 379 LDP parliamentarians were found to have ties to the Church. Even the LDP’s opposition, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDP), was confirmed to have at least 14 members linked to the Church, including a former leader of the party. According to an online survey carried out by Asahi Shimbun, a total of 447 respondents, made up of political actors including lawmakers, governors and assembly members, admitted they had some affiliation to the UC, with 80% of these Diet and assembly members being associated with the LDP. Of these 447 respondents, 41 admitted to having received assistance from the Church in election campaigns, and a further 23 conceded that they had accepted political donations or profited from the sale of fundraising party tickets by Church participants.

The UC held a much stronger political influence than any religious organisation should have, eroding the wall of separation between Church and State. But what about its popularity among the citizens of Japan? The Church itself claims that its Japanese members make up 600,000 out of 10 million members globally, which would equate to 6% of its members. This figure is disputed by media outlets which claim they only have around 100,000 active Japanese members. Yet it is reported that Japan has traditionally accounted for up to 70% of the Church’s wealth, an astronomical sum especially considering how much smaller a proportion of the Church the Japanese make up. Naturally, this begs the question as to how and why the Church became so successful – the answer lies in its impressive recruitment techniques.

Deceit, Propaganda or Preaching?

Image: Unknown (distributed via CC BY-SA 4.0)

The teachings of the UC are rooted in Christianity, though it is taught through the lenses of Moon, who claimed he had a vision of Jesus Christ where he was instructed to complete Christ’s unfinished tasks. The Church preached that Korea was the ‘Adam nation’ and Japan, the ‘Eve nation’. Moonism claims that mankind was burdened by the original sin which entailed Satan seducing Eve, who then had intercourse with Adam in the Garden of Eden, consequently producing a ‘Satanic bloodline’. Moon claimed himself to be the sinless, ‘perfect’ Adam, destined to create a sinless bloodline through marriage with the perfect Eve. This supposedly enabled him to choose which other couples could do the same, restoring mankind to its ‘original goodness’. Members were taught that their birth parents were satanic, and that Moon and his wife were their true parents, and thus their obligations fell to the latter. The premise was that Japan had betrayed Korea through its numerous invasions, and now the Japanese had to atone. It was this belief that enabled the Church to persuade Japanese women to be obedient towards their Korean husbands. According to former UC member Steven Hassan, Moon preached ‘openly about how lying was fine for God’ and that ‘you can control people by making them dependent on you, and that will allow you to dictate policy to them’. This ideology underpinned the Church’s approach to recruitment and control over its members.

Aside from religious doctrine, the UC would actively recruit members through various means. The Church would target single youths by conducting a ‘young people’s awareness poll’ via street interviews, going door-to-door, or inviting them to a ‘video centre’. Then, they would be subject to a 12-volume culture course, and numerous training sessions such as the ‘New Life training’. Next, they were urged to become dedicated members of the Church, being paid roughly a mere 150 USD a month despite having the duties of full-time UC staff. The Church also instructed its members not to inform their families about their conversion, and, once they were devoted enough, they would cut all ties with their families. This was one of the biggest obstacles for Church members considering defection. Defection rates for fully indoctrinated participants did not even reach 50%, and a large part of this was due to them having no communication with their families or friends, making a post-Church life seem very difficult as well as unappealing; the Church was, in effect, all they had. This issue was exacerbated by the meticulously structured Japanese employment system which made it next to impossible to rejoin the workforce once one had left it: the Japanese system tended to offer lifetime employment to fresh college graduates, which meant that those who had been out of employment, and those who had not freshly graduated were nearly always excluded. The Church members certainly fit this category.

Ultimately, the aim was to pressure their Japanese members to donate large sums of money to erase the ‘negative ancestral karma’ – this tactic was called ‘Reikan Shōhō’, which translates to ‘Spiritual Sales’. The Church was wildly successful in Japan on a financial front. Yet the intricate details of their exploits must be discussed to gain a full grasp on why the Church, after being shoved into the limelight by Yamagami’s actions, has come under great scrutiny by the Japanese public and media.

Japan: the UC’s Money-Making Machine

Image: Sky News

Arguably the most infamous of the UC’s many controversies was the mass marriages conducted by the Church where Japanese members donated upward of $14,000 to participate. In particular, single female members were coerced into marriage, going abroad to start families, and consequently budding the UC’s second generation, ripe for exploitation and indoctrination. Thousands of couples were matched, sometimes even through pairing photographs of people who had never met – perhaps an indication that the Church’s priorities were not to miraculously unite supposed soulmates, but rather to dredge out donations to cover their financial struggles. Though many members would eventually regret their marriage, they felt they could not terminate it as the UC reminded them that they, and potentially even their loved ones, would suffer immensely in this life as well as the afterlife should they make that choice. By the 2000s, approximately 7,000 female Japanese members had left for Korea to get married.

In addition to the mass marriages, another source of funding came from the UC’s sales of spiritual items such as pots, seals and scripture at exorbitant prices since the 1980s. In 2009, the president of the company selling seals (who was also a UC follower) was arrested, resulting in the Church issuing a compliance declaration, which Tanaka described as a ‘turning point’ for the organisation. The National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales disputed this, reporting that they handled 34,537 consultations on damages caused by donations and spiritual sales between 1987 and 2021, which totalled around 123.7 billion yen. Though the number of complaints declined after 2009, there were still 2,875 consultations between 2010 and 2021, with damages amounting to approximately 13.8 billion yen. After Abe’s murder, the number of consultations per month rose to over 100 a month.

The Cult Conundrum: Yamagami’s Paradoxical Deification

Image: Kremlin.ru (distributed via CC BY 4.0)

Though Yamagami’s actions must ultimately be condemned as reprehensible, it would be ignorant and naive to say that it did not have its positive impacts. His actions cast a blinding light onto the Church’s many controversies, exposing the damage it caused over many decades in Japan. It brought awareness to the children of members of the UC, who had often been neglected, and received little help due to the government and school officials being hesitant to interfere on the grounds of religious freedom. In addition to this, over 55,000 people have signed a petition advocating for legal protection for ‘second generation’ followers who claim they were forced to join the Church.

Possibly as a result of some of the positive impacts of Yamagami’s crime, combined with his torturous upbringing and perhaps even the fact that he is part of the ‘lost generation’ of Japan (a generation that suffered severe unemployment due to Japan’s miraculous economic bubble finally bursting, setting in motion decades of stagnation that persists today), Yamagami has become a rather popular figure amongst certain sectors of the Japanese population. Around 13,000 people signed a petition requesting prosecutorial leniency for Yamagami which was sent to Abe’s murder trial. Additionally, A group of internet-based worshippers, the ‘Yamagami girls’, have also elevated him to the status of a ‘noble vigilante’, reportedly sending him food, gifts and money to his jail cell, and describing him as a ‘god of the lower classes of Japan’.

When pondering the public perception of the UC, it is certainly telling that Yamagami’s violent solution was so well-received by Japanese society, a society that typically has zero tolerance for crime. Perhaps the surprising outpour of sympathy for the killer of Japan’s longest-serving Prime Minister stimulated the Japanese government to finally deal with the church that had exploited and manipulated the nation for decades. Yamagami’s crime served to be quite detrimental for the Japanese government – the approval rate for Fumio Kishida, the current Japanese prime minister, plummeted from 63% at the time of Abe’s death, to roughly 29% in September of 2022 amid growing concerns over the LDP’s links to the Church. Kishida’s reputation has not recovered since, with his cabinet approval rate being recorded at around 22% in December of 2023, though this further decline was likely exacerbated by a recent fundraising scandal. Nonetheless, the government has attempted to deal with the Church through various legal channels, though tangible results may take years.

On his quest to salvage his government, Kishida stated in August of 2022 that ‘as far as I am aware, I have no ties to the Unification Church’. Kishida also reshuffled his cabinet, purging members with ties to the UC. Additionally, the national police agency chief resigned, taking responsibility for Abe’s death. However, none of this was particularly rewarding for Kishida, who remains immensely unpopular with the Japanese public.

Moving away from power politics, the Japanese government has also attempted to hold the UC accountable. The issue of spiritual sales has had a turbulent history in the courts of Japan, with a Fukuoka district court finding the UC ‘legally liable for the unlawful acts for the procurement of monetary donations’, ordering them to pay 300,000 USD in 1994. Yet these cases never seem to hold much regard given the Church has continued its shady, exploitative operations. Taro Kono, the Japanese consumer affairs minister, held the first meeting with a panel focused on the Church’s ‘dubious transactions’, which included spiritual sales, to explore what can be done within the framework of the law, as well as possible recommendations to the government on how to deal with the UC.

In October of 2023, after a year-long investigation, Kishida’s government asked the court to strip the UC of its religious status. If the court accepts this, the organisation would lose ‘exemptions from corporate and property taxes, as well as a tax on income from monetary offerings’. Given the Church was already so reliant on Japanese donations, a lack of tax breaks in addition to the dwindling donations caused by the intense, and generally negative public attention the Church received since Abe’s assassination would place further duress on the UC’s finances. Making a recovery in every sense seems very difficult, whether it be financial or reputational. However, even if stripped of its religious status, there are concerns that the Church may ‘continue to operate in a new incarnation’.

In December 2023, Japan’s parliament passed a bill to monitor the assets of the UC in order to ‘ensure relief to its victims’. The legislation serves two main functions: the first is to prevent the UC from moving its assets abroad, due to the expected compensation it will have to pay to victims; the second is to help the victims of the UC, advocating for the use of the Japan Legal Support Center, and providing a system to temporarily cover the fees to lawyers regardless of their income and assets.

Overall, the Japanese government has undertaken many different initiatives to try to combat the UC, even though it is likely that it has done so due to public pressure. Naturally, the UC has attempted to defend itself, offering an assorted mix of apologies, excuses and some compensation.

The Church’s Defensive Doctrine

Image: FCCJ

Tanaka has made multiple statements attempting to steer the narrative in their favour. He denied ‘political interference’ with any party, claiming that the Church was only close to the LDP due to their shared anti-communist stance. He also ‘expressed remorse’ over the Japanese government's request to dissolve the religious organisation, arguing for religious freedom and organisation. He also accused the media and lawyers of ‘persecuting Church followers’. In line with this, around 3,500 Church members protested in Seoul against what they labelled as ‘discriminatory and unfair Japanese media coverage’ over the UC.

The Church, in addition to public statements, has also begun to issue some refunds, stating that they plan to offer up to 10 billion yen in compensation. They also claim to have dealt with 664 refund requests worth roughly 4.4 billion yen between the period of July 2022 to November 2023, as well as having apparently returned around 400,000 USD to Yamagami’s mother. Despite this, lawyers supporting victims of the Church believe that the total could end up being around 100 billion yen, ten times more than what the Church has allocated thus far.

This complex blend of defence, remorse, and negotiation sets the stage for a broader reflection on the consequences of this saga – not just for the Church, but also for Japanese society and its political landscape as a collective.

Navigating the Aftermath: Concluding Thoughts

As we stand at the confluence of these tumultuous events, it becomes clear that the assassination of Abe, while a solitary, despicable act of violence, rippled far beyond its immediate shock. It catalyzed a national reckoning with the pervasive influence of the Unification Church, an entity that had discreetly nestled itself within Japan’s political fabric and its citizens’ lives.

The assassination of Abe, while certainly a dark chapter in Japan’s history, has served as a catalyst for introspection and change. It has compelled society, the government, and religious entities to confront uncomfortable truths and navigate a path towards healing and reform. The lasting impact of Yamagami on Japan’s socio-political landscape will be a subject of observation and analysis for many years to come, as the nation grapples with the delicate balance of faith, power, and justice.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of The PublicAsian.

Comments ()