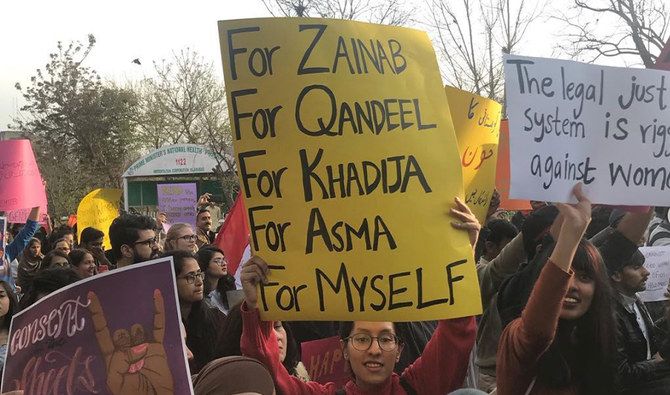

Justice Denied: Judicial Corruption Against Women in Pakistan

Judicial corruption, legislative failures, thousands of unsolved cases and the absence of justice for rape victims – these elements compose Pakistan's "justice" system. In such bleak circumstances, is there any hope for the women of Pakistan?

The System: A Breakdown

The judicial system in Pakistan is based on common law, seeking its origins from the British colonial era. The system is divided into three levels of courts: lower courts, high courts, and the Supreme Court, respectively increasing in the power hierarchy.

There are also two specialised courts: the Federal Shariat Court which ensures that the principles of Islam are in accordance with the laws, and the Anti-Terrorism Court which deals with cases related to terrorism. However, unlike the British common law jurisdiction, Pakistan has no jury trials, which has encouraged negative sentiments as a result of feeling excluded in the process of reaching justice in a democratic regime.

The System: The Truth

But what is Pakistan’s judicial system actually like? It is widely known for its social-status-based justice, where religious minorities and women are discriminated against in courts, the police only work on bribery, and there is an extreme lack of legal aid and awareness of individual rights. Numerous studies and reports have provided evidence for the lack of preservation of the rule of law and judicial corruption in Pakistan: The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2022 ranked Pakistan 129th out of 139 countries for its overall rule of law score, with criminal justice being placed at 97th rank and civil justice at 125th. Furthermore, an evaluation conducted by the National Judicial Policy Making Committee of Pakistan found more than two million cases are pending in the Supreme Court, Federal Shariat Court, high courts, and the district judiciary.

The Pakistan Lawyer, a blog aimed at raising awareness about the law and the legal system in Pakistan, described the Pakistani judiciary as “a corrupt judiciary where bribery prevails and the rich have the upper hand”, suggesting that justice is often elusive for the poor and vulnerable. A disturbing example of this is when a wealthy man assaults a poor girl, the victim faces numerous hurdles before her plea is ever heard. Firstly, the police may not file a crime report, as the victim's family cannot afford to bribe them, while the perpetrator can. Oftentimes the victim or the police are silenced by money or threats of further violence. Moreover, in many small districts, cultural bias and a sense of shame lead to the family members or villagers murdering the victim. Even if the crime is eventually reported, it is unlikely to be heard and prosecuted for years due to a significant backlog of cases in the system. Even so, the chances of the perpetrator receiving punishment are incredibly low due to, again, rampant bribery and corruption within the courts.

The Rape Epidemic

A country where the issue of rape is still very much a stigma, Pakistan is plagued with what can only be described as a rape epidemic. Data collected by the Punjab Home Department and Ministry of Human Rights shows 21,900 women were reportedly raped from 2017 to 2021. This figure, however, is only the tip of the iceberg, with many cases going unreported due to the social stigma and fear of violence. Recent studies and evaluations have found that a woman is raped every 2 hours in Pakistan. However, these figures do not correlate with those of the prosecution. War Against Rape, a non-profit organisation, found the conviction rate in rape cases to be less than 3%. Moreover, reports conducted by the United Nations Development Program concluded Pakistan to be the top country holding an anti-women bias in courts, explaining the lack of justice for heinous crimes committed against females, such as the case of Kainat Soomro.

The Rape of Kainat Soomro

In 2007, Kainat Soomro was only 13 years old when she was kidnapped and gang-raped by four men for three consecutive days before escaping and returning to her family. When her brother went to the local police to file a report, “the police sided with the village leaders and refused to act.” Dadu, the village where Kainat resided, was ruled by a tribal system, which is not uncommon in Pakistan, whereby rulings are declared by elderly powerful villagers without the crime ever reaching formal judicial courts. The elders suggested declaring Kainat an “outlaw” and “impure”, ordering her death in the name of karo kari (an honour killing), blaming the woman for a man’s crime and threatening her family with punishments if they rebelled against this verdict.

Fearing for their lives, Kainat’s family fled to Karachi where Women Against Rape, a Pakistani organisation, decided to help Kainat’s case, bringing it to media attention. Due to public outcry, the four men were arrested and imprisoned without bail and the case finally reached the courtroom. However, due to the police’s lack of early action in gathering evidence, it was difficult for Kainat to prove her statements. Though a medical examination provided proof of sexual intercourse, no sperm test was taken as the hospital lacked the facilities to do so. Furthermore, the defence stated that one of the alleged rapists, Ahsan Thebo, is Kainat’s husband, and that they were married at the time of the incident. They argued Kainat had a love affair with Ahsan, and due to her parents’ disapproval, they eloped and got married. They supported these claims with a marriage certificate that Kainat argues was coercively signed by her at gunpoint. This defence is very common in Pakistan, whereby men, after raping women, force them into marriage in order to justify their actions later on.

In 2010, after three years of hearings and trials, the court gave the verdict of not guilty, acquitting the four men and accepting the defence of marriage following Shariat law. The judge proclaimed Kainat’s statement as a flimsy and fantastical made-up story. With the four men now free, the family received many threats demanding Kainat be with Ahsan as his wife:

“I’ll take her from them, whenever I get the chance, no matter what. If Kainat marries anyone else, I’ll kill him and I’ll kill her.”

Months after the verdict, Kainat’s brother Sabir Soomro was found dead. The family suggested that the alleged rapists were involved in his death in an attempt to silence Kainat. However, after only four months, the police closed the investigation of Sabir’s death, declaring there to be a lack of evidence and foundation required to reach a conclusive resolution.

Undeterred, Kainat filed a criminal acquittal appeal, still fighting for justice. However, this is still pending adjudication before the Sindh High Court and could take many years before being heard by a judge.

‘Honour’ killings

Pakistan Penal Code 1860, Section 299 defines an honour killing as any offence committed in the name or on the pretext of karo kari, siyah kari or other similar customs or practices. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan reported approximately 15,222 cases of honour killings between 2004 and 2016. Mariyam Suleman Anees of The Diplomat writes:

“According to the Human Rights Watch, the most common reason for honour-related crimes is the violation of social norms and what is thought to be accepted social behaviour. A woman’s choice of clothing, employment, or education; her refusal to accept an arranged marriage; getting married without her family’s consent; seeking a divorce; being raped or sexually assaulted; having intimate or sexual relations before or outside marriage, even if only alleged – these are seen as valid reasons for an honour killing.”

Until 2016, the killers could escape punishment if the victim pardoned them. This was possible due to the principle of Diyat under Section 310 of the Pakistan Penal Code, which allowed victims or legal heirs of the victim to pardon the perpetrators for blood money. Often, victims would be pressurised to do so, such as in the case of Saba Qaiser, where after being shot and dumped in the river by her father and uncle for marrying against their will, the 19-year-old pardoned their legal sentence due to family pressure. However, the Criminal Law (Amendment) (Offences in the Name or Pretext of Honour) Act passed in 2016 made minimum prison sentences mandatory. This reform was sparked by a high-profile case that received vast media attention, where a 26-year-old celebrity was murdered by her brother in the name of honour – Qandeel Baloch.

The Murder of Qandeel Baloch

Fouzia Azeem, famously known as Qandeel Baloch, was a Pakistani actress and social media influencer. She came from a working-class background, and at the age of 17 was forced into marriage by her family. Soon after, she gave birth to her son. Due to her husband’s alleged abuse, she fled with her son to a women’s shelter in Multan. Qandeel’s husband denied all accusations. Unable to financially support her son, she returned the child to her husband who accepted this responsibility under the condition that Qandeel signs a written agreement renouncing child custody forever. Qandeel agreed to this, which was not considered honourable in her family, leading to them cutting all ties with her. Consequently, she moved to Islamabad and changed her name from Fouzia Azeem to Qandeel Baloch and decided to pursue a career in show business.

Qandeel started working as an actress in advertisements and television series. However, she gained most of her popularity from social media, due to her sexually provocative videos which caused wide controversy in the Islamic state. The situation escalated following her viral interview with a senior cleric and member of Pakistan’s religious council, Mufti Abdul Qavi. During the interview, the two were seen flirting, with Mufti Qavi suggesting they meet the next time he visits Karachi. Following his invitation, the two met in a hotel in Karachi. They were seen having playful interactions, such as Qandeel wearing the Mufti’s cap through the videos and pictures taken and published by Qandeel, perhaps in an effort to expose his hypocrisy and to demonstrate that he is not as pious as he claims to be.

This spread like wildfire, causing massive controversy and subsequently, the suspension of Mufti Qavi from the religious council. Qandeel, on the other hand, received heavy media backlash and death threats, along with the disclosure of her real identity and family background, causing her family stress and social pressure. This was the final straw for her brother, Muhammed Waseem. When Qandeel returned to her family home in order to escape the chaos, Waseem strangulated her to death in the name of honour. He confessed to the media that he decided to kill her following the emergence of her pictures with Mufti Qavi:

“I gave her sleeping tablets and then I strangled her… I have no regrets. She was bringing dishonour to our family. Girls are born to stay home and follow traditions. My sister never did that.”

In 2019, Waseem was sentenced to life imprisonment. However, he was acquitted in February 2022 after being pardoned by his parents and Waseem’s appeal claiming that his confession in 2016 was coerced by the police. This court ruling “brought the campaign for justice for Ms Baloch back to square one.”

Despite the 2016 legislative amendment that mandated imprisonment for honour killings, the murderer of Qandeel Baloch roams free. The legislative change failed to make an impact, as the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan reported over 470 cases of honour killings in 2021. However, human rights defenders estimate around 1000 women are killed in the name of honour every year, with little to no consequences for the offenders. This poses the question of what the future of Pakistan will be, when justice is so temporary and patriarchal customs continue to corrupt the judicial system. Why is it that a woman was killed for being dishonourable, whereas the murderer and the man triggering the ‘dishonour’ continue to live with respect? Why did only the woman receive punishment for breaking traditional social norms, when the man was also involved in the incident? Although there has been legislative revision, honour killings continue to happen, demonstrating the need for cultural change in Pakistan. As Qandeel’s father rightfully questioned, how could a murder in the name of honour ever be honourable?

The Future of Pakistan

From police failure to report crimes, to judges being bribed in courts, the ceaseless corruption in Pakistan seems like a dead-end for many, losing hope in a system which keeps failing them. Recent years have seen an increase in public outrage, calling for a deep-rooted reform. However, with an unstable political system and the government’s lack of concern for the judiciary, this seems like a will-o’-the-wisp idea. How can any country prosper when the justice system is anything but just?

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of The PublicAsian.

Comments ()