Rebranding a Nation: Japan's Erasure of their Imperialist History

Japan’s image has transformed significantly from the World War II era. How this radical change came about was not simply the product of Japan’s affinity in such sectors, but rather also a deliberate enforcement of propaganda by the Japanese government in order to reimagine Japan’s hostile history.

Disclaimer: This article contains sensitive topics.

Japan’s image has transformed significantly from the World War II era. Formerly known as an aggressive nation bent on conquest, Japan is now seen as a hub for technology innovation and an appealing array of media, including anime, pop music, and idol culture. How this radical change came about was not simply the product of Japan’s affinity in such sectors, but also a deliberate enforcement of propaganda by the Japanese government in order to reimagine Japan’s hostile history.

Japan’s Role in WWII

In 1940, Japan allied itself with Nazi Germany and the Kingdom of Italy, forming the Axis Powers. Together they fought in WWII against the ‘Big Three’ – the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union. From 1931 to 1945, Japan would occupy Manchuria, Beijing, Nanjing, French Indo-China, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Burma, and Malaya. However, it was Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941 which solidified its reputation as an aggressor in the eyes of the West.

1894: Japan occupies Korea and Taiwan following the First Sino-Japanese War

1931: Japan invades Manchuria

1933: Japan withdraws from the League of Nations

1937: Japan takes Beijing and Nanjing following the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. This is the height of Japan’s war atrocities, including various war crimes and the Nanjing Massacre

1939: Japan occupies French Indo-China

1941: Japan’s Attack on Pearl Harbour results in 2,403 deaths

1942: Japan takes the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Burma and Malaya

1945: The US bombs Hiroshima and Nagasaki in retaliation, resulting in an estimated 100,000 to 300,000 deaths

The Comfort Women System

The Comfort Women structure was a conscription system in which an estimated 50,000 to 200,000 women were drafted as essentially sex slaves for Japanese soldiers. These women were parts of the societies that the Japanese occupied during the WWII era, with a significantly large amount hailing from Korea. The issue of comfort women in Japan was almost unheard of until the mid-1990s, when Korean women began to disclose their experiences with Japanese soldiers. The Japanese government immediately renounced the accusations – the House of Councilors’ Budget Committee asserted that an investigation into the matter of comfort women would ‘not yield any results’.

After international pressures to conduct more thorough investigations, the Japanese government apologised in the 1990s for the sexual exploitation its military participated in during the war. However, women who have contributed towards global awareness regarding the comfort women system have been met with death threats, bomb threats and online harassment (including doxxing and cyberbullying) by Japanese neto uyo (ultranationalist Japanese internet activists). Additionally, influential Japanese leaders have continued to justify the use of comfort women, or to deny the existence of the comfort women system entirely.

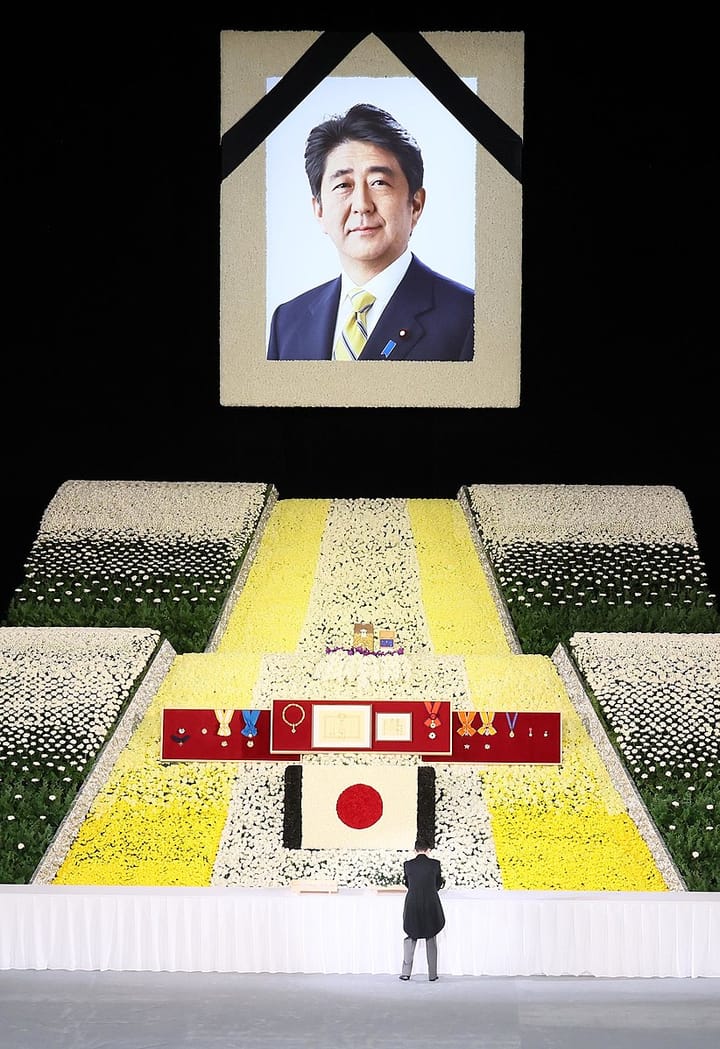

In 2013, the Mayor of Osaka stated that the comfort women system was ‘necessary’ to ‘maintain discipline’ among Japanese soldiers. In the same year, the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also attempted to revise the Kono Statement previously made by Japan’s PM in 1993 acknowledging and apologising for the sexually exploitative system. These comments have undermined Japan’s efforts to atone for its war atrocities, and to reconcile with the Republic of Korea particularly.

The Hundred-Man Killing Contest and The Nanjing Massacre

On the march to Nanjing in 1937, two Japanese officers, Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda, hosted a ‘hundred-man killing contest’ – both men competed to see who could kill 100 people by sword first. Later on, the two men would again compete to kill 150 people.

On December 13th 1937, Japanese forces pushed into Nanjing, China. Over the course of 6 weeks, the Japanese army would destroy Nanjing by looting and committing acts of arson, while murdering, torturing, and raping the citizens of Nanjing. An estimated 200,000 Chinese were killed, along with the rape of 20,000 women and children. According to firsthand accounts, the murders were not swift; Japanese soldiers tortured their victims in an extremely explicit manner, which this article will not detail due to its immensely disturbing and sensitive nature. Nevertheless, Japanese officials have continued to defend or denounce the existence of the Nanjing Massacre.

Rewriting History

Despite Imperial Japan’s numerous war atrocities, a survey conducted by Tokushi Kasahara revealed that, while 79.2% of Japanese students surveyed agreed that the Nanjing Massacre occurred, 58.82% of students had ‘no idea’ about the hundred-man killing contest, and 29.36% either did not know or underestimated the number of people killed during the genocide. This uncertainty can be attributed to the Japanese government’s deliberate efforts to reimagine Imperial Japan’s history.

Textbook Exclusions

Japanese textbooks used in the school curriculum are not written by government actors themselves – rather, textbooks are created by private companies, supposedly to ensure students are provided with a syllabus free from nationalistic sentiments. However, Japanese textbooks must undergo an ‘authorisation system’ to determine that the content is ‘objective and impartial’.

As a result of the Textbook Authorisation System, the Japanese Ministry of Education has rejected textbooks which portray Imperial Japan negatively, such as those which explain in detail the atrocities of the comfort women system and the Nanjing Massacre. Instead, some approved textbooks have reduced both events to a single footnote each, along with the bombing campaign in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to just a single sentence. In fact, in one edition, only 5.3% of its content covered the years 1931 to 1945, despite the period arguably being the most significant in Japanese history. Japanese textbooks which have successfully passed the authorisation system, such as the New History Textbook (2000) have even gone so far as to emphasise Imperial Japan’s colonial ‘achievements’, while censoring elements which may damage Japan’s reputation.

The Shinzo Abe Administration

Shinzo Abe has been repeatedly accused of perpetuating a false narrative of Japanese history. As early as 1990, Shinzo Abe accused China of fabricating the reality of the Nanjing Massacre in order to defame Japan – he asserted that the number of casualties was exaggerated and that it was really the Chinese who had committed mass genocide against the Japanese.

Concerning comfort women, in April 2007, the Japanese government attempted to run a full-page advertisement in the Washington Post which denied the events of the Nanjing Massacre, citing the photo evidence as ‘doctored’, and asserted that such accusations were spearheaded by the Propaganda Department of the Chinese Nationalist Government. When the Washington Post refused to run the advertisement, the Japanese government then tried to clarify their stance on the comfort women issue – denying that the Japanese military forced women into prostitution, but that comfort women were instead ‘paid extremely well’.

Shinzo Abe was also a prominent member of the Nippon Kaigi lobbying group – an ultra-right, ultra-nationalistic organisation that not only denied Japan’s WWII atrocities, but also believed that Japan’s imperialism in fact liberated East Asian countries from European colonialism. During the Shinzo Abe administration, over half of the Japanese cabinet, and 60% of Japan’s Parliament were members of Nippon Kaigi.

Rebranding Japan

In the early 2000s, Japan’s transformation from an ‘aggressor’ began. Despite the high global demand for Japanese military technology due to its former status as a great power, Japan instead invested in its entertainment industry, perhaps in order to redirect the global perception of Japan as a hostile nation, to a non-threatening one. This new era in Japan became known as ‘kawaii’ (cute) culture.

Cute culture in Japan took various forms – anime, manga, Japanese idols, and character licensing were the main elements of pop culture in Japan. In promoting the new vision for Japan, the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs lent support for globalising the industry in 1997, particularly in entering the American market. Thus, Japanese characters and franchises such as Pokémon, AstroBoy and Godzilla began to take their place as household names worldwide. Despite Japanese products being perceived as ‘rip-offs’ during the WWII period, Japanese consumer electronics began to take the world by storm. Following the collapse of the American video game market from 1983 to 1985, Japanese company Nintendo took its place with vigour, accumulating 10 million sales. Japanese brands such as Sony, Mitsubishi and Panasonic were quickly prominent actors in the electronics market.

Some critics argue that Japan’s inclination towards pop culture is simply natural in Japanese culture. Author Matt Alt argues that Japan has cultivated an artisan spirit (shokunin), which allows Japanese art in all its forms to contribute something never before seen to the world. True as that may be, the fact remains that the Japanese government utilised the craft to their political and economic advantage – 'Cool Japan'. Cool Japan is a government initiative, aimed at creating a new perception of Japan. Deliberate or not, Cool Japan distanced the nation from the war crimes of its imperial ancestors. David Zax warns that Japanese pop culture fanatics in the West or otherwise may manifest into a ‘sympathetic response to Japanese people as a whole’.

Conclusion

Japan’s fixation on boosting their entertainment and technology industries was a deliberate effort by the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry to enhance their global soft power. As cute culture and technological advancements in Japan grew exponentially, the world no longer associated Japan with their war atrocities, but rather with their affinity for novelty. With the addition of the Japanese government’s refusal to take accountability for, or even acknowledge their wartime cruelty, Japan has somewhat successfully erased its imperial history from the world.

By Ashvini Prem

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of The PublicAsian.

Comments ()